GoToData Dashboard’s screening tool shows us that only 75% (1464) of all TSE1 firms have nom + com committees, but only 842 of them are chaired by outside directors. At only 51 of those firms does an outside director serve as chair of the board, and 44 firms in that group have at least one female board member. Below, read more of the interesting results from this demonstration of the screening tool.

Month: May 2022

The General Counsel as Board Member – Advice from Larry Bates, Former General Counsel at Panasonic, Lixil, and GE Japan

In Japan, traditionally there was no role of “General Counsel” (GC), the senior in-house counsel/lawyer, who sometimes sits on the board. Instead, until recently the standard model was that companies had a “Legal Department” led by a general manager who normally was not a licensed lawyer, and therefore had less to “lose” if he failed to give proper advice or transgressed ethical and other rules set by the Bar Association. However, as Japanese companies have expanded and globalized, more of them are realizing that it is essential to have an actual licensed attorney serve as the “Chief Legal Officer” (CLO), serving a broader, more senior, and influential role.

In this webinar, BDTI’s Nicholas Benes will interview the well-known Larry Bates, who recently stepped down from his role as Panasonic’s first General Counsel and will retire as a director in June of this year. During the past 30 years, Larry has served as General Counsel for 30 years at five different companies, all of which operated in a global legal context. To provide actionable advice and perspectives to Japanese companies, the interview will focus on key issues such as: (a) what should be the GC’s role and mission, and how does the concept of “GC” differ from the traditional Japanese model? (b) should that role include “corporate secretary” duties, or should the two roles be kept separate? (c) what other functions does it overlap with, and how should the GC relate to them? (d) what are the pros and cons of having the GC sit on the board? What is his or her relationship with the board and other executives? (e) what legal or compliance matters do Japanese companies need to pay more attention to? (f) what is it like to participate in board decision-making itself, not only as GC but also as a foreigner, on a Japanese board? What can be done by Japanese companies to benefit more from diversity? – to name just a few.

After the interview, there will be a panel discussion including other experienced legal advisors and independent directors at global companies. We will be joined by Chika Hirata, currently Regional Head of Ethics and Compliance at Takeda, and the former CLO and Corporate Secretary at MetLife Japan; and by Yumiko Ito of Ito Law Office, who also serves as an independent director for Kobe Steel, Ltd. and as an independent corporate auditor for Santen Pharmaceutical, Co., Ltd.

This event will be held in English.

Governance Around the World: Japan (Video of Webinar)

In this webinar hosted by the Good Governance Academy of South Africa, the institutional characteristics of corporate governance in Japan were compared with other countries and the progress of the Japanese corporate governance reform since 2013 was highlighted. In particular, the changes that have occurred in Japanese companies and capital markets, as a result of recent reforms in corporate governance, were discussed, including by Genta Ando of METI, together with how these changes have been perceived in Japanese society. Finally, the actual state of corporate governance in Japan was reviewed considering Japanese company corporate disclosures, with commentary by Professor Mervyn King.

The Other Side of the Coin – Changes in Japanese Equity Price Formation From 2000-2021

by David Snoddy, CEO of Nezu Asia

SUMMARY

The nature of Japan’s relationship with equity market capitalism changed significantly from the first decade to the second of the 21st century. The first decade, particularly after the resignation of PM Koizumi in 2006, was often characterized by open conflict, with the most obvious examples being the arrest and conviction of shareholder activists Horie and Murakami, and the legal and regulatory attacks on both the consumer finance and leveraged real estate businesses (among others). However, approximately around 2011, the attitude of both government and the public morphed into something more resembling symbiosis than conflict. In the third decade of this century the symbiosis mode seems still to be ascendant.

Many of the top-down aspects of this shift have been well documented and discussed both in Japan and in the West – from the 2015 Corporate Code, to the 2014 Fiduciary Code and the emerging catalysts created by the rule set for Tokyo’s new “Prime” market. From the perspective of governance per se, there have been some concrete steps “backwards” (with the Toshiba drama a prime example). However, the cumulative effect of the change in the regulatory suasion regime in Japan is such that it is difficult to find equity market participants who believe that the governance environment in 2021, on average, is not noticeably more shareholder-friendly than it was 10 years ago.

Over the same period there has also been a dramatic shift in trends in Japanese equity price formation. This is not well documented or understood. But it is in fact the micro expression of the same impulses which are driving the “macro” changes in the regulatory regime. Since 2011, there has been a marked change in how the market “votes with its feet” – rewarding companies who conform to the new desired profile, and punishing those who don’t. Specifically, capital efficiency and, to a slightly lesser extent, revenue growth, have captured outsized returns.

The top-down changes in the regulatory regime are on one side of the coin. The bottom-up changes in price formation are the other side of the same coin.

The socio-economic function of equity capitalism in Japan is somewhat uncomfortably positioned between two massive sources of pressure. On the one hand, the aging of Japan’s society is slowly turning active employees into pensioners who, either directly or indirectly, depend on financial income to maintain their living standards. This economic pressure provides the core motivation for the changes in Japan’s approach to equity capitalism – both from the top and the bottom. One the other hand, there is a near-consensus social desire to protect and maintain the lifetime employment system, albeit only for a subset of employees. Predictably, these two pressures are often in conflict, which accounts for some of the peculiarities of “equity capitalism with Japanese characteristics.”

The social commitment to maintain the lifetime employment system predates all of the data to be presented here. The demographic challenges posed by the aging of society have been building for a generation or so, but it was only after 2011 that they resulted in a shift towards a noticeably more cooperative approach to equity markets.

METRICAL: How Far Corporate Governance Has Progressed in 2021 (4) – Change in ROA and ROE and Corporate Governance Practices

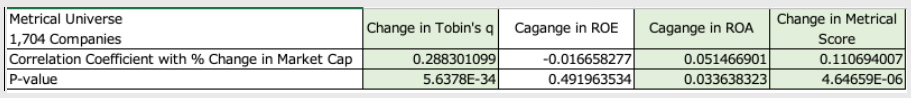

In my previous article, “How far has corporate governance progressed in 2021 (3),” I discussed the results of a correlation analysis between the percentage change in market capitalization as of December 2020 and December 2021 for 1,704 companies in the Metrical universe and the respective changes in Tobin ‘s q, ROA, and Metrical Score, respectively. The results of the analysis showed a significant positive correlation between the percentage change in market capitalization and the respective percentage changes in Tobin’s q, ROA and Metrical score, as shown in the table below.

In this article, I would like to focus on the question of why the percentage change in market capitalization has a more significant positive correlation with ROA than with ROE. As you know, ROA is a measure of a company’s earnings power, while ROE can be increased by changing the capital structure to match that earning power. This means that ROA can be directly impacted by improving business performance, while ROE can be increased without necessarily relying directly on improving business performance. In this article, I would like to examine whether there has been any change in the corporate governance practices of the companies whose ROA has improved (and thus whose market capitalization tends to increase).

The table below shows the percentage change in ROA for 1,704 companies in the Metrical Universe as of December 2020 and December 2021, correlated with each of the Corporate Governance Practices. The table below shows the results separately for Board Practices and Key Actions. There is a significant positive correlation between the cash holding score and the dividend policy score among the key actions that the company actually takes, and a significant negative correlation between the growth policy score and the rate of change of ROA in one year in 2021. It could be argued that a company is not motivated to change its board practices because of a one-year change in ROA. On the other hand, for key actions, we found that when ROA changed over the year, the company tended to reduce cash by increasing dividends. Although further analysis is needed to determine the significant negative correlation between ROA change and growth policy, it may be inferred that the cash accumulated in the balance sheet due to the increase in profits was used to return profits to shareholders through dividend increases, but the use of cash to invest in growth is still lacking in conviction.