Here is the short speech that I gave to the Fall 2016 Conference of the Council of Institutional Investors (CII), on September 30, 2016. On this video, my speech starts at the 36:00 minute point. Below, I have reproduced the CII’s summary of my comments, and further below, the full text of my speech.

” Nick Benes, representative director for the Board Director Training Institute of Japan, said a sea change is underway in Japan in terms of companies beginning to comply with the Corporate Governance code, but there is still room for improvement. He reported that almost 80 percent of Japanese companies now have two or more independent directors and 40 percent of large companies have their own corporate governance guidelines, but beyond that, the reforms that companies say they have in place are lacking in substance. He estimated that 90 percent of firms say they comply, but have little evidence this is the case and few have actually changed their practices. Despite these setbacks, Benes said he remains optimistic that Japanese companies will move in the right direction because there is now broad awareness that “governance is good”. Additionally, disclosure has vastly improved and the number of votes opposing the re-election of directors is climbing. A video of this session is available here. ”

Text of Speech (and Slides)

“In 2013, I was lucky enough to propose to key congressmen in Japan, that Japan should have a Corporate Governance Code. I then advised them, and then the Financial Services Agency, about the content of the Code.

So I am very pleased to have this opportunity to summarize the progress that Japanese companies have made so far in implementing the principles of the Code, based on my activities as consultant, independent director, “directorship” trainer, and policy advocate.

My main message to Committee members is this:

1) A sea change is underway in companies, the media, the government, and the public. Because Japan is a “shame-based” society, the vastly enhanced disclosure required by the Code has created a strong virtuous circle.

2) These changes represent a very big opportunity for foreign investors, but only IF they study the Code and the disclosures in detail, and then leverage the Code’s principles so as to make specific requests for better governance practices to Japanese companies they invest in, while also brandishing the possibility of consequences – such as not re-electing senior executives, – if progress is not made.

Here are some highlights “from the trenches” about what is occurring in Japan:

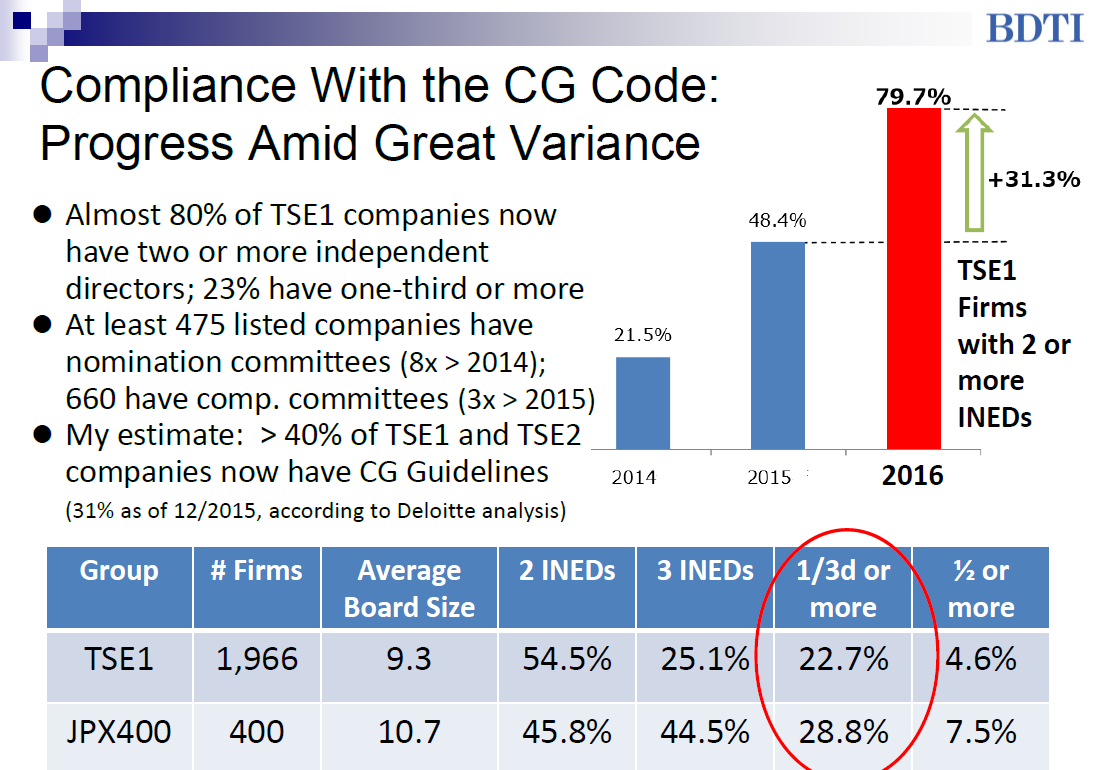

First, after what is really only one year into the Corporate Governance Code reporting cycle, about 80% of companies on the first section of the Tokyo Stock Exchange now have two or more independent directors on their boards. We can argue about the independence of some of these, but at about 23% of these companies 1/3 or more of the board is now composed of external directors who are disclosed as being “independent” according to an ascertainable definition.

Second, there has been a very significant increase in the number of companies with nomination and compensation committees, even though such committees are not technically required by the Code, but are only suggested as an option.

Third, I would estimate that about 40% of all companies listed on both sections of the TSE have publicized “corporate governance guidelines” of some form, written in their own words. These also are not actually required by the Code, but they show that many companies understand that they cannot claim in their reports to the stock exchange that they have clear policies about nominations, board evaluation, director training etc. , unless such policies are actually written down somewhere. In short, there is increasing recognition that actual substance has to be put in place.

Given where we were two years ago, in the context of Japan, these are very significant, irreversible changes. Essentially, the concept of “best practices” that aspire toward constant improvement, has finally arrived in Japan. Said another way, the Japanese manufacturing concept of “kaizen” – continuous improvement – has come to the field of governance. At the same time, the Code has armed those internal executives who already wanted better governance and decision-making at their own firms, to make their case much more effectively.

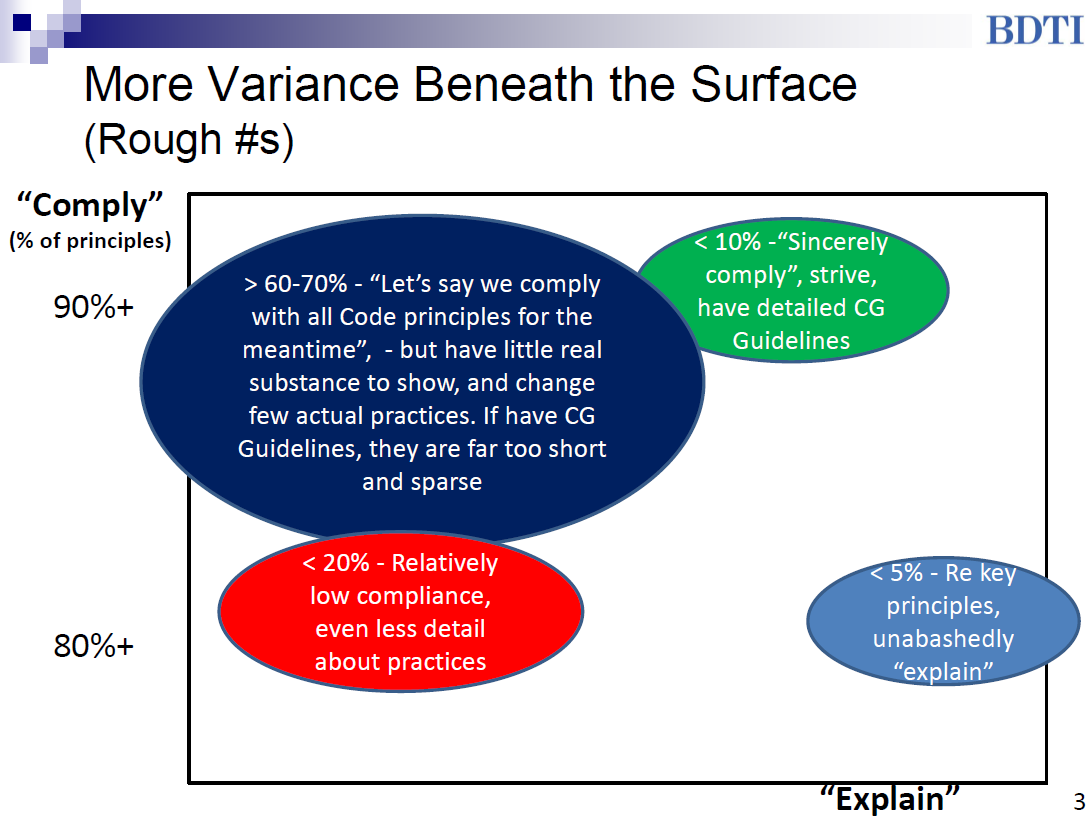

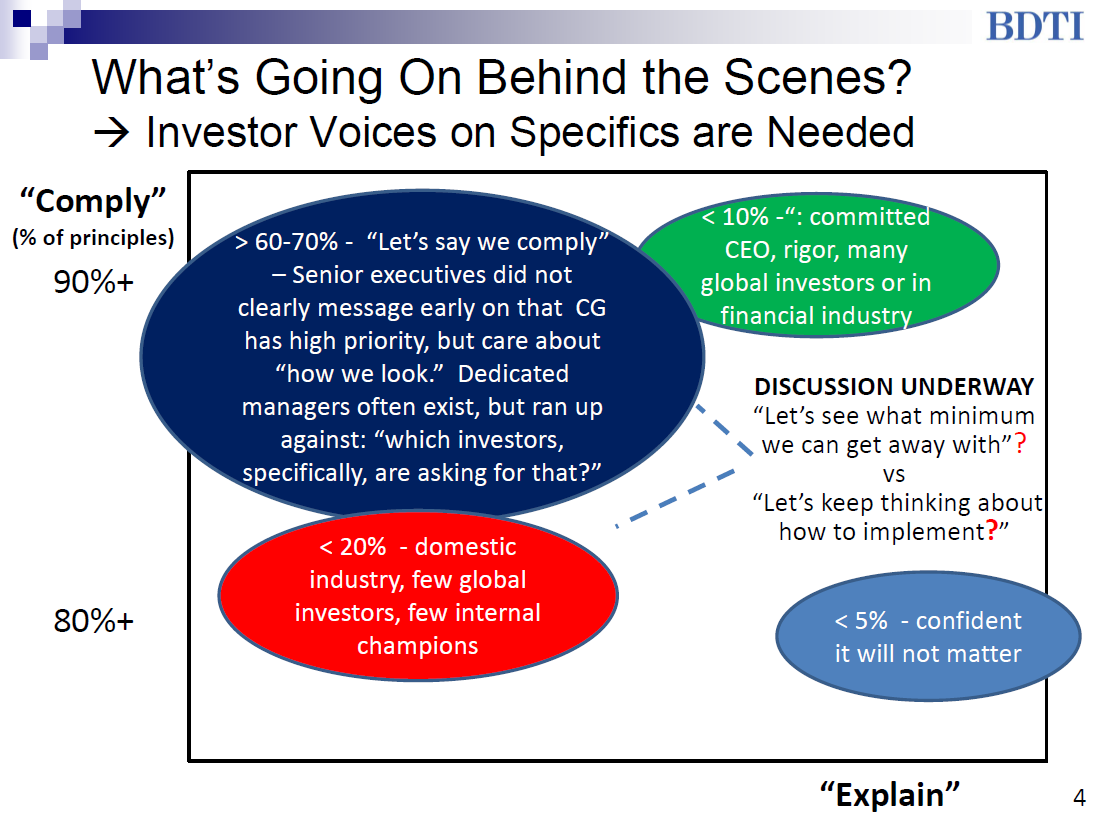

However, when you look at individual companies and what investors expect when they read the Code, there is still great variance. There are of course those firms who essentially already “got it”, and are trying to look even more like leaders. These are companies like Omron, ORIX, Shiseido, Hitachi and the major bank groups. But many companies – I would say, 60 to 70% of TSE listed firms – are still in flux. Up until the first reporting deadline date of last December, in many cases these companies scrambled to make some of the important changes. They very much wanted to say “we fully comply with the Code”- because they suddenly realized they would be embarrassed if they could not say so. But in fact, in many cases the procedural infrastructure, and understanding of the practices, had not been put in place yet. And since many of the practices were new, learning and acceptance of their logic was needed. This does not take place overnight. As a Japanese friend of mine says, “in many cases, they are basically lying.”

But the good news is, in many of these companies, things did not stop there. This year there is still discussion underway, in a tussle between those persons who think more serious, sincere implementation is needed, and those who in a sense, are saying, “let’s just see what minimum we can get away with”. In this tussle, two things are most important: first. the stance of senior executives and the independent directors, and second, – understandably – “what are investors actually asking for”? When I act as a consultant to help design corporate governance guidelines for companies, that is the question that gets shot back by CEOs or Senior Managing Directors. “Who, specifically, is asking for an independent nominations committee, or a meaningful director training policy?” If our internal team can only respond with, “well, it is considered a best practice”, we will immediately lose the argument. But if we can point to several shareholders who have specifically asked for those things, we stand a good chance at winning.

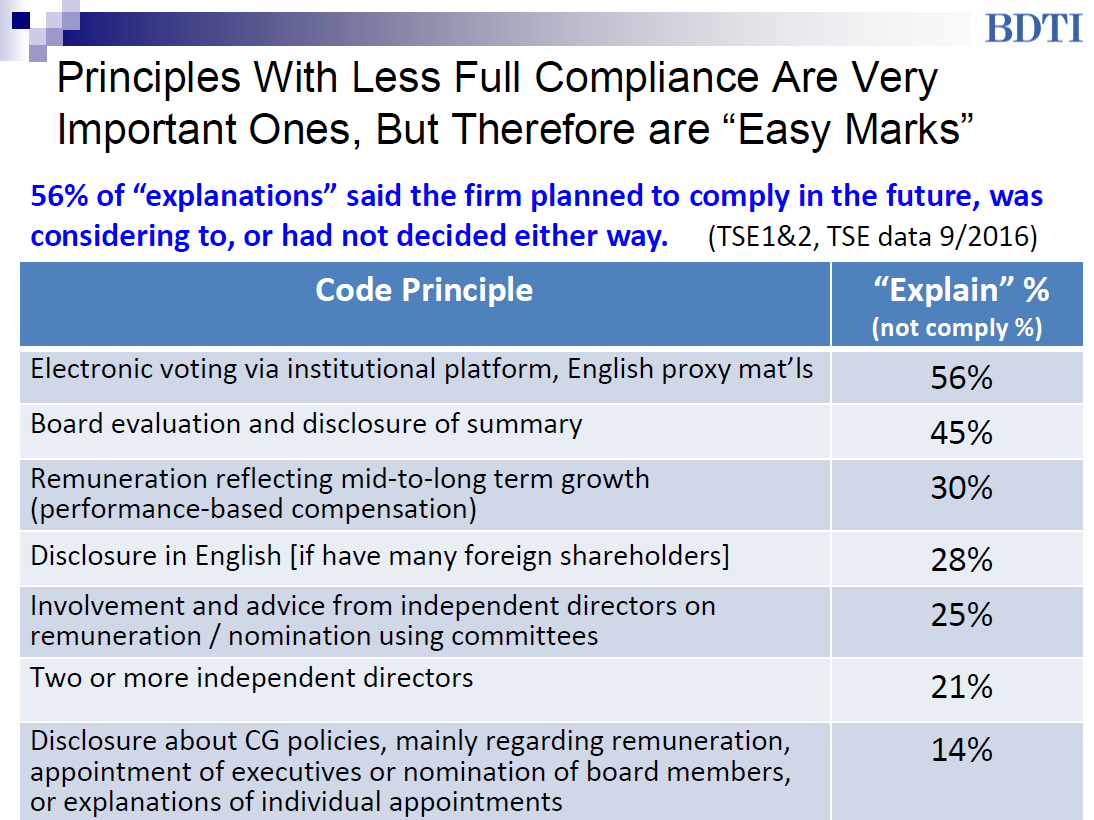

Among all 2,500 Tokyo Stock Exchange firms, these are the Code principles that have the highest incidence of companies “explaining” their non-compliance, after the June 2016 AGM season. The numbers would be lower, BTW, if we were only looking at the first section of the TSE. You may say, “but Nick, these are the most important principles!”, – and I know, I know, because I myself proposed most of them. But here is the upside: a majority of companies “explain” that they are considering to implement these principles, or have not decided to not implement them.

And for investors who engage with companies actively, most of these are easy marks to some extent, because they are so eminently reasonable. If many of your investors are foreign, why do you not use the electronic voting platform and produce materials in English? Does the board evaluate everyone in the company, except itself? Do you not care about having a more effective board? What is the sense in having independent directors if you do not use committees, given that they are in the minority? And so forth. There are very strong logical arguments for these practices, and they can now get some traction, because other companies have adopted them.

So the upside potential is definitely large…., and in a shame based society, the new disclosure, transparency, and acceptance of governance as something “good” are positive factors that are creating an virtuous circle in Japan. To executives who are very sensitive to negative reporting, the fact that the media now tries to report on governance-related events with an eye to “what does this say about the quality of governance at this firm?” has a deep potential impact. ROE is the buzzword of the day, and the number of books about corporate governance has quadrupled. There are now many positive factors at work.

But Rome was not built in a day, and bringing about behavioral and practice changes in large organizations is not easy. It requires a lot of new learning, discussion, and constructive prodding from the outside. How much upside is obtained, will depend largely on foreign investors, because domestic institutions in Japan will tend to follow them and learn from them.

So here is my advice. Investors can now have real positive impact if they point to the Code, set forth priorities based on it, and clearly write down specific practices they would like to see implemented…. and if at the end of those letters, they write, for instance, that “if we do not see robust practices like these in 15 months or so, we may consider voting against certain senior executives who are up for re-election.“ This is what will get the attention of Japanese companies at the senior level, which is where it counts.

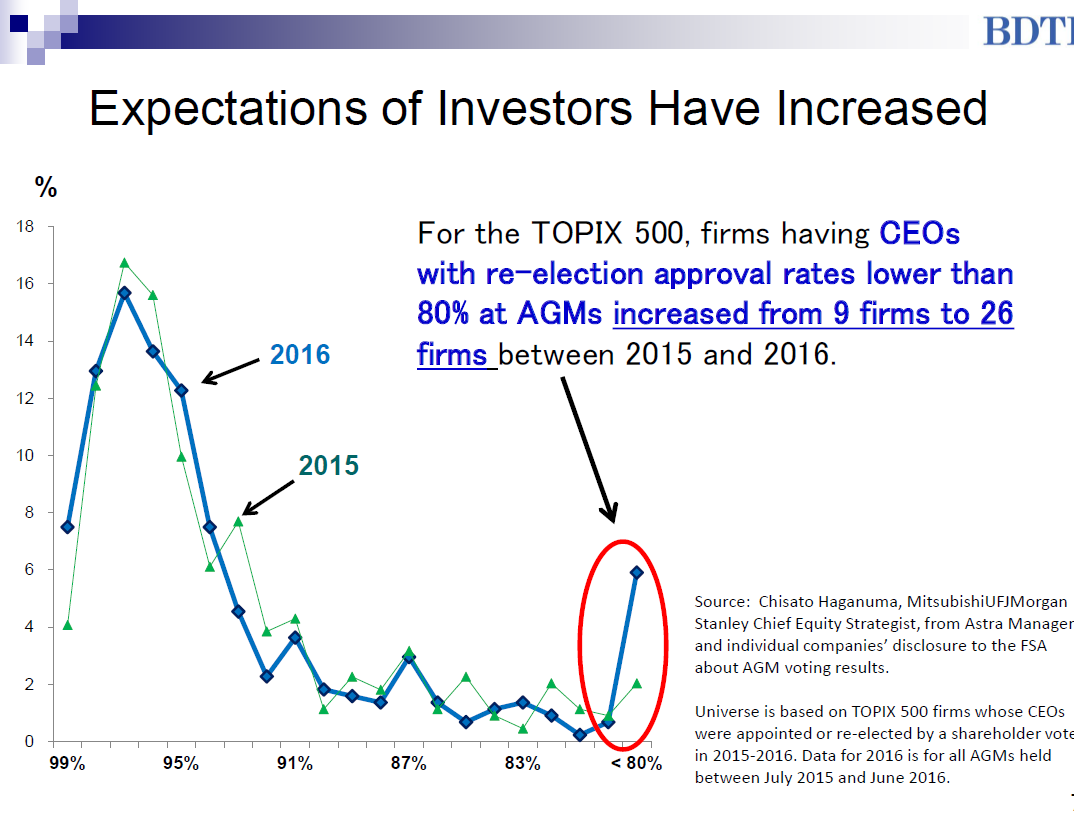

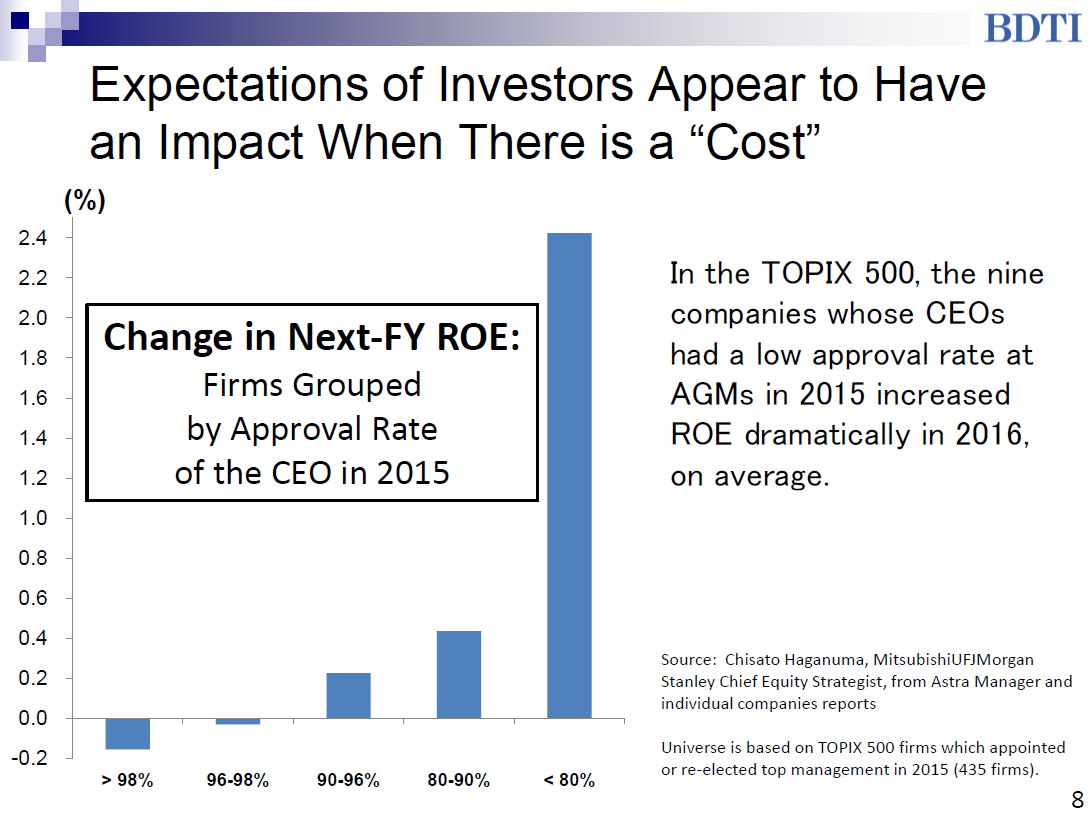

This is already starting to happen. Last year, at only 9 companies in the TOPIX 500 did CEOs up for re-election get approval from less than 80% of voting shareholders, which is a level that indicates a clear vote of no-confidence. This year, the number was 26 firms. And for some strange reason, as if by magic, the 9 firms where CEOs got weak support last year, found a way to improve their ROEs by 2.4% on average this year.

Thank you very much, and please feel free to contact me later with any questions you may have. ”

Posted by Nicholas Benes