The current Whistle-blower Protection Act was enacted in 2004 and was enforced in 2006. It was said that the scandals of the recall cover-up by Mitsubishi Motors and the disguising of the origin beef by Snow Brand Foods brought on the new Act. However, from the beginning, there was criticism: that the range of targeted facts was too narrow, the prevention measures for retaliation were not effective, and such. Based on the supplementary resolutions of the Diet and the supplementary provisions of the Act, the Consumer Commission Whistle-blower Protection Special Research Committee was established, and discussions began with a view to revise the Act. However, the speed was very slow. The Committee finally issued its report in December 2018. Public comments were solicited for the new appendix table to the Act regarding the targeted laws. The amendment bill was approved by the Cabinet on March 9, 2020. It is now planned to be submitted to the National Assembly.

The main amendments of the bill are including the following:

- Whistle-blowers include corporate directors (directors, officers, accounting advisors, auditors, etc.) and retired workers within one year of their retirement (Article2, Section1, Item3 and 4).

- Broader protection coverage for whistle-blowing to government agencies, etc. and news media, etc.

- Stipulation of the criteria for dismissed corporate directors to demand payment of damages to the company (Article 6)

- Stipulation of a rule that the whistle-blower shall not be liable for damages due to whistle-blowing (Article 7)

- Obligation for companies to establish an internal reporting system (Article 11)

- Confidentiality obligations placed on whistle-blower responders, and fines for violations (Articles 12 and 21)

In this article, I would like to describe how the terms of the revised bill will affect directors and auditors of a company (together hereinafter referred to as “company directors”) when they become whistle-blowers.

Article 6 categorizes company director/whistle-blower into three types: those who make internal reports to companies (No.1 Report), those who make external reports to government agencies, etc. (No.2 Report) and those who make external reports to news organizations, etc. (No.3 Report). Then, each are defined as follows:

- In case a corporate director is dismissed on the grounds that a No.1 Report was made, he/she is entitled to claim damages caused by dismissal. The corporate director only needs to “think” there was the occurrence of an urgently report-worthy fact.

- In order for a corporate director who has performed a No.2 Report to government agencies etc. to recover damages, only “thinking” is not enough. The law requires them to ① take an effort to conduct ” investigative corrective measures ,” and yet to have ② “reasonable grounds” to believe that a report-worthy fact has occurred or is about to occur and there is a state of urgency (No .2A Report). Or there needs to be ② “reasonable grounds” to believe that report-worthy fact occurs or is about to occur in a state urgency, and there shall be ③” reasonable grounds ” to believe that damage to personal life, body or property is occurring or is about to imminently occur (No .2B Report).

- In case “reasonable grounds” ② and ③ are justified, a company director who has made an external report to the news media is entitled to damages recovery (No. 3B Report). However, ① ” investigative corrective measures ” and ② “reasonable grounds” are not sufficient for a No.3A Report. An “Additional Special Reason” is needed: (1) “reasonable grounds” to believe that he/she would receive disadvantageous treatment; (2) ”reasonable grounds” to believe that the evidence would be destroyed if whistle-blowing is done internally (only); or (3) he/she is told not to report, without any justifiable reason.

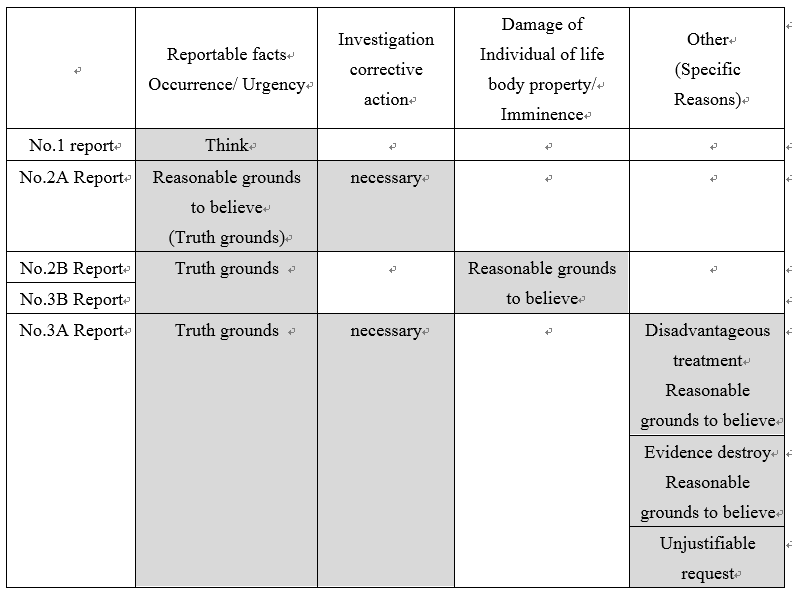

The following table summarizes the protection requirements for claiming damages.

Let’s think of an example case by simplifying and modifying the Olympus Case. Mr. A was the president of UK subsidiary Y, and promoted to be the president and the representative director at Tokyo head quarter of X Inc. Just prior to the promotion, a magazine published an “investigative journalism” article claiming that X Inc. was hiding a loss, and that the collaborators of this wrongdoing were anti-social forces. Mr. A knew of the article, and requested PWC to investigate. The requested PWC report came back saying that the article’s conclusions were probably true, but it was difficult to draw definite conclusion without internal investigation. Mr. A requested by e-mail an answer from the chairman and other directors regarding the truthfulness of the article and the internal investigation, and notified them that he would ask the company’s own audit firm to make further investigation. The chairman strongly opposed Mr. A. He convened the Board of Directors, which dismissed Mr. A on the grounds of “arbitrary conducts.” Mr. A, who remained a non-executive director, was afraid of the anti-social forces, and hurriedly returned to London. He was interviewed by the Financial Times regarding the alleged loss concealment, and reported what he knew to the UK Serious Fraud Office. X Inc. told major players in mass media that it would sue Mr. A over the “information leakage”. X Inc.’s share price plummeted, the chairman resigned, and Mr. A resigned as a director. Then, the third-party committee investigation uncovered hidden losses.; X Inc. received criminal and administrative punishment for making securities report misstatements; and the chairman was convicted. Mr. A sought 10 years of salary as compensatory damages for r unfair dismissal in the employment court in London. Mr. A settled with X Inc. and received about four years of compensation (£ 10M). Four years after the settlement, subsidiary Y sued over Mr. A’s pension (£ 64M), alleging Mr. A orchestrated its terms so as to be advantageous to him, hiding his intention from the Board of Directors. Three years later Mr. A won this lawsuit in court. The UK Serious Fraud Office conducted investigations over the loss concealment carried out in the UK, but its efforts were unsuccessful, and the investigation ended after two years. It should be noted that the person who provided a magazine with information was Mr. C, an accounting department employee of X Inc. Mr. C did not contact himself/herself with reporters for fear of retaliation, and provided information to Mr. B, the sales personnel of X Inc., who was already a whistle-blower for other issue and on bad term,s with the company.

If this example case is applied to the amended Whistle-blower Protection Act, what kind of protection would Mr. A receive? First, Mr. A “thought” that there was a report-worthy fact and reported it to the chairman and other directors. This action will meet the protection requirements of No.1 Report. Companies must not treat whistle-blowers in a disadvantageous manner (Article 5 Clause 3). Note that the shareholders of X Inc. cannot remove Mr. A from the president office. However, they can remove Mr. A from the board. (According to Article 339, Clause 1 of the Companies Act, companies are free to remove directors by a resolution of a general meeting of shareholders.) After such dismissal, Mr. A would be left only with right to claim remuneration for the remaining period of his term as a director, according to said Article Clause 2 and Whistle-blower Protection Act Article 7.

Let’s consider whether Mr. A ‘s external reporting to Financial Time meets the protection requirements. The PWC report has great significance, here. The contents of the report seemed to support the “reasonable grounds” for Mr. A to believe that the reportable facts occurred. Was the PWC report sufficient for the “investigative corrective measures?” The chairman refused further investigation, the board agreed with the chairman, and fired Mr. A as CEO and president. With all board members opposing, even if Mr. A was still a director, it would have been virtually impossible to investigate further or take corrective action. I would construe that the report met the requirements for investigation and corrective measures. The Chairman objected to Mr. A ‘s report to the audit firm, and Special Reason was granted. Mr. A fulfilled the protection requirements for No. 3B Report.

Were the protection requirements of No.3B Report met? “Individual” as in individual life, body or property, in principle, means individuals in terms of the public interest. If the false statement in the securities report is the report-worthy fact, “individual” means an investor or shareholder who has suffered property damage, and this damage has occurred. However, we cannot forget the imminent danger to the whistle-blower’s own life and body. I would like to think it appropriate to construe whistle-blowers themselves to also be considered as “individuals. ” Whistle-blowers may feel that they are in danger of being injured by the people who feel harmed by the information whistle-blowers obtain. In that case, the only way for whistle-blowers to protect themselves is to disclose the information. Harry Markopolos, who found the Ponzi scheme by Bernie Madoff, reported to the SEC, but the SEC ignored his report. Madoff is the big shot in the securities industry, some of whose customers are likely money launderers. Markopolos felt danger from them, possessed a pistol and checked his automobile for bombs when he drove. I would like to consider Mr. A, in this respect, also met the protection requirements of No. 3B Report.

It is interesting to consider whether reporting to the UK Serious Fraud Office met the protection requirements of No.2 or not. If Mr. A reports to the Japanese investigation authorities, it will meet the protection requirements of the government agencies, etc. (No.2 Report). However, it is unknown whether reporting to foreign administrative agencies is within the scope. Large companies have internal regulations that define whistle-blower protection and their regulations are often applied to foreign subsidiaries as well. Reports made by employees of overseas subsidiaries to foreign governmental agencies will also be protected by companies’ internal regulations. However, it seems that is it is not frequent that those internal regulations cover corporate directors.

To summarize the above, at least Mr. A satisfied the protection requirements related to the internal report (No.1 Report) and the external report to the news organizations (No.3 A,B Reports). However, there is another issue for Mr. A to claim X Inc. for damages. Mr. A has resigned, not been fired from X Inc. Mr. A has settled with X Inc. in the Employment Court in London. But what if he filed and tried a lawsuit at a Japanese court seeking damages based on the Whistle-blower Protection Act and the Companies Act? Does the “dismissal” stipulated by laws include “unavoidable resignation?”

X Inc. told that it would sue Mr. A seeking damages due to information leakage. Whistle-blower Protection Act Article 7 prohibits the claims against whistle-blowers, who are satisfying Article 6 of protection requirements, for the damage cause by whistle-blowing. It is not uncommon that companies claim damages caused by whistle-blowers as a counterclaim. The activities causing those damages are conceivably of two kinds; (i) an information acquisition, and (ii) an information leakage. Whistle-blowers first suspect of the facts to be reported based on the information they obtain naturally in their line of business. As they suspect further, in order to whistle-blow, they may be in need to access the information which they have no access authority, or to copy the information for other than business purposes. This is a problem of type (i). Also, whistle-blowing can damage to a company’s reputation and cause considerable damage. This is the problem of type (ii). Article 7 seems to cover only (ii), the latter. The report of the Committee has separated sections for ” 4. Responsibility for collecting data to support reports” and ” 13. Liability for damages due to reporting.” Article 7 seems to have the intention to only cover the latter. It seems that appropriate activities out of (i), the information acquisition, would hopefully be protected by the general doctrine of the individual court handling each case.

The litigation, X Inc. filed regarding Mr. A’s pension for damages, was not related to the whistle-blowing. It could not be said that it violated Article 7. Mr. A would see this as a retaliation by X Inc. for his making a report in the public interest. However, these lawsuits, except for the frivolous kind, cannot be stopped. By the way, the pension of Mr. Woodford in Olympus case, shares some similarity with the understatement of compensation of Mr. Carlos Ghosn in Nissan case, in the sense that that compensation will be received after the retirement from the Board of Directors. Mr. Woodford had worked for KeyMed, Olympus ‘s great-grandchild company, as an employee and an executive director for more than 30 years. It must have seemed to the UK court that the expensive pension amount was legitimately based on the pension plan of KeyMed, and not the problem. On the other hand, the disclosure of compensation paid to Mr. Woodford as the Representative Director of Olympus, in the securities report for the fiscal year of March 2012 (Before correction) is shown as follows: basic remuneration 101,074 thousand yen, bonus 38,000 thousand yen, retirement benefits not described. It is not certain that the pension from the great-grandchild subsidiary of the company after long service as an employee should be disclosed in the securities report of Olympus. However, if Mr. Carlos Ghosn’s understatement is a problem, I wonder if Mr. Woodford’s pension (£ 64M) could have been a problem, too.

We have been observed how the revised Whistle-blower Protection Act Bill protects corporate directors as whistle-blowers in an example case similar to the actual one of Olympus. Are reports to the foreign government agencies protected? Are directors who are forced to resign rather than dismissed protected? These aspect remain unclear. In particular, the former point is interesting. Today, company activities are globalized. There could be the cases where report-worthy facts happens abroad, or where the foreign reporting is more effective than domestic one.